September 2, 2025

The “gas boom” legacy has turned into an “infrastructure bust” challenge. Policymakers, engineers, and financiers are urgently seeking a new formula to finance renewal.

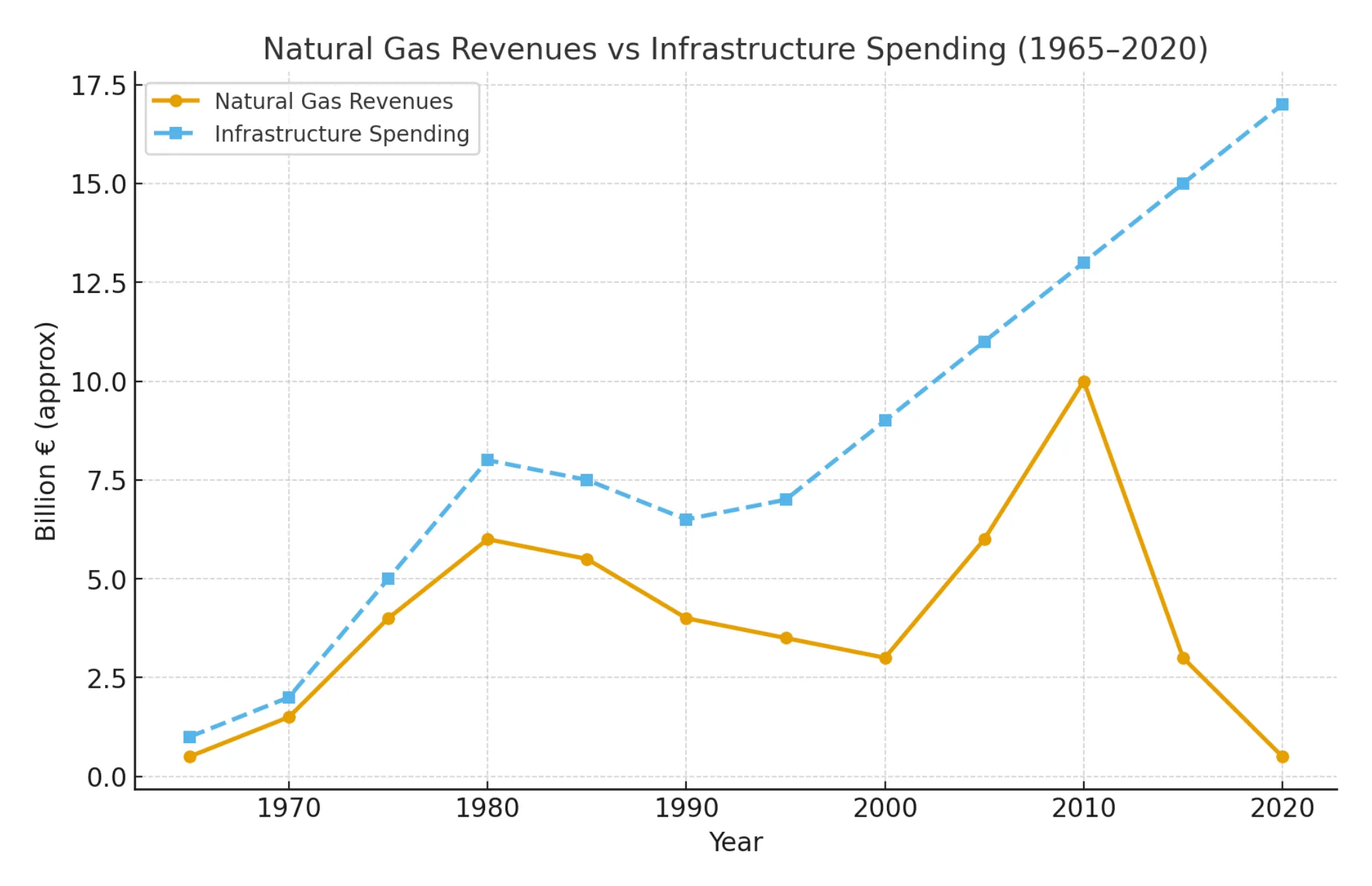

In the 1960s, the Groningen gas field transformed the Netherlands’ finances. Discovered in 1959 and developed through the 1960s, Groningen yielded a gusher of revenue for the Dutch state. Over the decades, the government earned an estimated €265–428 billion from natural gas extraction . At its height in the 1980s, nearly 20% of the national budget was funded by Groningen gas income . This windfall helped make the Netherlands “one of the richest countries in the world,” financing an expansive welfare state and ambitious public works . Landmark infrastructure projects – from new highways to the colossal Delta Works flood barriers – were built during this era, effectively underwritten by gas revenues.

The government treated gas money as general income, funding various ministries’ programs. Notably, in the late 1990s the Economic Structure Enhancing Fund (FES) channeled €26 billion of gas proceeds into projects like the Betuwe freight railway and high-speed rail lines. However, unlike Norway, which invested its oil profits into a sovereign wealth fund, the Dutch did not set aside a national gas fund. Analysts later calculated that if the Netherlands had emulated Norway’s approach from the start, it might have amassed a €350 billion fund by 2014 (with an annual €13 billion payout). Instead, the gas riches flowed directly into the treasury – a decision that expanded public spending but left no large financial buffer for the future.

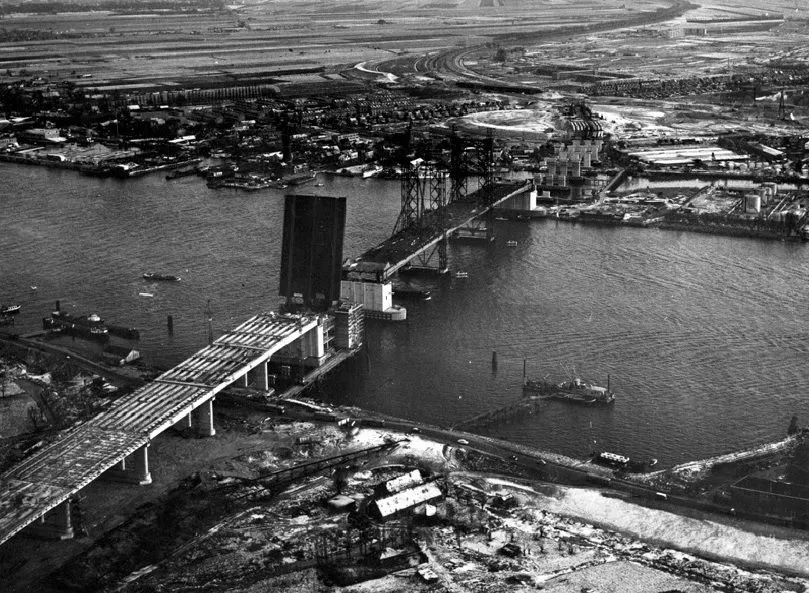

Van Brienenoordbrug (Rotterdam) – an iconic 1960s highway bridge – now requires an urgent €1.5–€2 billion overhaul as decades of heavy use take their toll.

The infrastructure financed by the gas boom is now decades old – and it shows. Much of the Netherlands’ vital transport network was built in the 1960s and 1970s, meaning bridges, locks, and highways are reaching the end of their design lifespans . Many structures face wear-and-tear far beyond what their engineers anticipated. Today’s traffic is heavier (both in volume and vehicle weight) than in the postwar years, accelerating the decay . Yet maintenance budgets haven’t kept up. In fact, years of austerity and political trade-offs led to deferred maintenance: in 2020, over 40% of municipalities said they cut back on infrastructure upkeep to save money. Local governments, which manage 80% of the nation’s roads, bridges, and canals, simply haven’t had the funds to reinvest in timely repairs . This has created a mounting backlog of work.

The scale of the maintenance shortfall is alarming officials and experts. The national public works agency, Rijkswaterstaat, warns it is short at least €35 billion over the next 13 years just to fix highways and major waterways . That implies a multi-billion euro gap annually. Indeed, Rijkswaterstaat admits it falls roughly €1 billion per year short of what’s needed for basic maintenance – current budgets of around €1.5 billion are nowhere near the €2.3–€2.6 billion required each year . Other infrastructure owners report similar strains: the rail network operator ProRail says it needs an extra €1.8 billion for overdue rail maintenance . Provinces and municipalities collectively face additional billions in unfunded repairs on local roads, bridges, and canal walls . In total, an enormous investment gap has opened up between the aging infrastructure’s needs and the money actually spent. Even the Minister of Infrastructure has bluntly stated that maintenance budgets are far too low to tackle the problem, calling it “quite a challenge” to manage vital bridges and motorways under current funding.

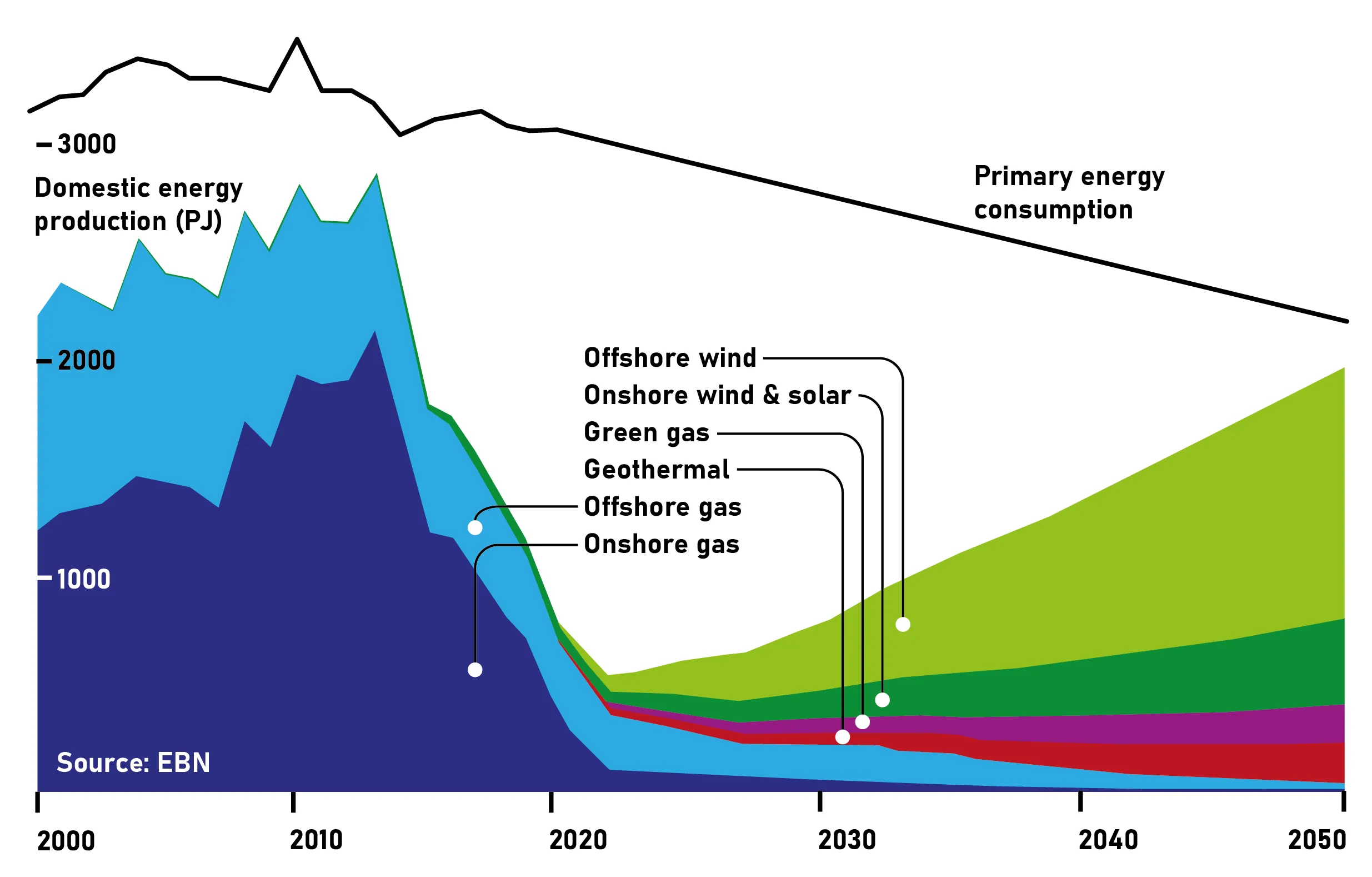

The timing of this infrastructure crisis coincides with a dramatic economic shift: the winding down of Groningen gas production. After six decades of pumping, the Dutch government moved to shut the giant gas field amid mounting safety fears. Years of extraction had triggered earthquakes – some over magnitude 3 – damaging thousands of homes in the Groningen region. Public outrage over quake damage and climate policy pressures finally forced The Hague to act. In 2022, authorities announced Groningen’s gas taps would be closed for good, and by October 2023 production effectively ended . This decision, though applauded by safety advocates and environmentalists, has abruptly cut off a major source of state revenue. As a result, the Netherlands can no longer count on easy gas money to fund big investments as it did in the past. The “free lunch” of the gas era is over, just as the country’s infrastructure repair bills come due.

This has thrust policymakers into fierce debates over new ways to finance infrastructure. One proposal high on the agenda is road pricing – specifically a mileage-based driving charge. The Dutch government has already approved a plan to introduce “kilometerheffing” nationwide by 2030, replacing the current road taxes with a per-kilometer fee for cars . The idea is that those who drive more will pay more, creating a fair usage tax and potentially reducing congestion. However, these plans were originally devised as revenue-neutral (swapping one tax for another) and aimed at climate goals, not as a huge net-new funding source for infrastructure. Even if implemented, the projected few cents per km charge may not fill the multi-billion euro gap in maintenance funds . As ABN Amro’s economists recently warned in a stark report, mileage charges “will not be enough” – a large financial gap will remain for overdue maintenance, renewal, and expansion of transport networks .

Banks, business lobbies and even some government advisors are now floating more radical ideas. In a notable shift, toll roads and waterway tolls – long taboo in the Netherlands – are being touted as a necessary solution to raise cash. ABN Amro’s study argued that tolling specific routes could “kill two birds with one stone,” managing traffic demand while generating dedicated revenue for upgrades . For example, charging tolls at busy highway pinch-points (perhaps only at peak hours) or imposing fees on ships passing key locks could both regulate congestion and fund repairs . Such user-pays systems would also spread costs more fairly, the bank noted, since currently electric-vehicle drivers pay little under fuel taxes . Congestion charges in city centers, similar to London’s, are another idea: economists suggest Amsterdam and other cities could levy fees on cars and even on canal usage to help fix crumbling bridges and sluices . Notably, Dutch banks and pension funds have signaled they’d invest in infrastructure if there are steady toll revenues as collateral – a model to attract private capital . “Toll revenues can serve as collateral for institutional financing from banks and pension funds,” ABN’s transport economist pointed out .

Political opinion on these measures is divided. The transport industry, for its part, seems open to tolls if the proceeds visibly improve roads. “The transport sector is not against tolls if it delivers results – as long as the proceeds are funneled back into road transport,” one industry representative said . But Dutch drivers and many politicians have historically resisted paying directly for roads. Past attempts at introducing road tolls or urban charging have provoked public backlash. For instance, when Amsterdam’s city government floated a plan to toll cars entering the center in 2018, national politicians swiftly shot it down. Members of Parliament from the ruling coalition declared that every city must remain accessible and vetoed any new toll, forcing Amsterdam to shelve the idea . Such resistance suggests that selling the public on new fees will be an uphill battle. Still, with the gas income gone and infrastructure visibly deteriorating, the political calculus may be shifting toward pragmatic acceptance that users may have to pay where general taxation no longer suffices.

Meanwhile, other stakeholders clamor for action. The construction sector warns that decades of under-investment cannot continue without dire consequences. Industry groups have urgently called for adding at least €4 billion extra per year to infrastructure budgets just to catch up . Technical experts at TNO (a Dutch research institute) estimate about €50 billion in additional spending will be needed in coming decades to restore and upgrade aging civil works . Provincial and municipal leaders argue they cannot tackle their enormous local replacement tasks alone . They are asking The Hague for dedicated capital grants or a co-funded program to rebuild local bridges and quays, noting that municipalities currently must cover these costs out of general funds often already strained by social services . The new Minister of Infrastructure, Barry Madlener, has responded coolly that local authorities must also “make tough choices” and prioritize infrastructure as “one of their core tasks,” implying that not all the help will come from the center . In short, everyone agrees on the urgency of repairing infrastructure, but who will pay – drivers, taxpayers, local or national governments, or private investors – is now a central economic debate in the post-gas Netherlands.

The toll of deferred maintenance is no longer hypothetical; it’s playing out in real time with surprising and costly infrastructure failures. In Amsterdam this summer, two major waterways were suddenly blocked after recently renovated bridges broke down . The Scharrebiersluis bridge at Kadijksplein, a critical link between the Amstel River and the IJ, had undergone a full overhaul in 2022–23. Yet by late 2025, the freshly upgraded bridge jammed shut and would not open, cutting off the shipping route . City officials were stunned that a brand-new rehab could fail so quickly. Amsterdam is now investigating the cause and considering holding the contractor liable under warranty . At almost the same time, another newly modernized span – the Ouderkerk Bridge over the Amstel – had to be closed for seven months despite a €46 million renovation just two years prior . Engineers discovered design flaws that require immediate fixing . These two closures left boat traffic into central Amsterdam with only one remaining route – which itself then got blocked when the old Willemsbrug at Haarlemmerplein failed to open . The domino effect of bridge breakdowns effectively choked off Amsterdam’s vital canal arteries, illustrating how frail some infrastructure has become. “These breakdowns reflect a national pattern,” ABN Amro’s report noted, as many bridges and locks from the 1960s–70s era are now faltering simultaneously .

On the highways, high-profile incidents are also sounding alarms. The Van Brienenoordbrug in Rotterdam – a double-arch bridge completed in 1965 (with a second span added in 1989) – is one of the busiest road bridges in the country and an essential artery on the A16 motorway. It is now slated for major renovation and partial replacement after periodic malfunctions and structural concerns. However, the project has turned into a cautionary tale of rising costs. Initially budgeted at €680 million, the Van Brienenoordbrug refurbishment is now estimated at €1.5 to €2 billion, triple the original figure . Rijkswaterstaat had to restart the tender when initial bids came in far above budget, and construction firms cited soaring materials prices and complexity . “Delaying the construction is not an option – it’s a very important traffic artery,” Infrastructure Minister Madlener said, underscoring the urgency despite the price tag . He publicly acknowledged that such overruns reveal the chronic under-budgeting of maintenance and appealed for more infrastructure funds . The bridge’s first arch (from 1965) will be entirely replaced, a stark reminder that mid-century structures are at their end-of-life . With ~230,000 vehicles crossing daily and 120,000 ships passing yearly , the stakes of a failure are extremely high – any extended closure would paralyze road traffic in the region and disrupt river shipping.

Every few weeks, news of some infrastructure glitch makes headlines: a lock gate stuck, a sinking quay, a highway overpass found with cracks. These incidents fuel public frustration and even safety fears. They also highlight an uncomfortable fact – stopgap repairs are less and less effective. In some cases, recently “fixed” infrastructure fails again quickly, wasting funds and eroding trust. The Brug Ouderkerk saga, for example, has angered locals and boaters who expected a fully functional bridge after years of construction, only to face another long closure. Such stories are eroding the complacency that Dutch infrastructure is always world-class. Political backlash is also in the mix: while people demand the government “do something” about crumbling bridges, they often oppose measures like tolls or tax hikes that would fund the fixes. This creates a tricky dynamic for leaders. The Amsterdam bridge fiascos, for instance, put pressure on city and national officials to invest more in maintenance, yet memories of the 2018 toll proposal – which provoked fierce opposition from multiple political parties and was swiftly abandoned – make politicians wary of angering voters. The result is a sense of urgency muddled with hesitancy, as the Netherlands grapples with a once-unthinkable question: could the country that engineered the Delta Works now see parts of its modern infrastructure literally falling apart?

The Dutch predicament also invites comparison to other nations’ experiences with boom-and-bust resource funding. Norway’s example looms large – Norwegians famously banked their North Sea oil riches in a sovereign fund, now worth over $1 trillion, providing ongoing returns for society. The Netherlands, by contrast, spent its gas windfall as it came; as one Dutch commentator bitterly noted, “if revenues from natural gas – €265 billion from 1960–2013 – had been invested like Norway’s, imagine the returns” . Germany offers another cautionary tale: when its coal industry waned, the German government poured funds into affected regions and introduced new infrastructure fees (like highway tolls for trucks) to ensure upkeep. In fact, nearly every neighboring country charges road tolls or has a dedicated infrastructure fund – something the Netherlands avoided during the gas-fueled years of plenty. These comparisons add pressure on Dutch policymakers to innovate their financing approach, lest the country fall behind in infrastructure quality. There is a growing realization that the “free ride” is over, and the Netherlands must find a sustainable model to renew its infrastructure for the next era.

Looking forward, the numbers leave little doubt: massive investment is needed to rehabilitate the Netherlands’ infrastructure, and the bill is coming due fast. Studies by engineers forecast that annual spending on just the replacement of old civil works must triple in the coming 15–20 years. Today, only about €1 billion is spent nationally on renewing bridges, locks, and tunnels; by 2040–2050 this will need to rise to €3–4 billion per year (in 2021 euros) to keep pace with aging assets . And that is in addition to the regular maintenance expenditures (inspections, minor repairs, operations) which themselves are expected to grow to around €7 billion each year . The overall peak of renewal costs is projected around 2080 as the last of the mid-20th-century structures reach the end of their extended lives . In the nearer term, a wave of replacements is looming between now and 2050. By one estimate, dozens of billion euros in extra outlays will be required by 2035–2040 to address the most critical works . For example, a TNO report projected that infrastructure replacement demand will rise steadily and already requires about €2.4 billion annually today, increasing to €3 billion by 2040 for local and regional works alone . If these investments are not made, the backlog and costs only grow – a classic “pay now or pay much more later” scenario.

Where could this money come from? A mix of new revenue streams and policy tools is on the table, each with pros and cons:

The consequences of inaction, meanwhile, are increasingly tangible. Rijkswaterstaat has warned that if the maintenance gap isn’t closed, the public will face more frequent disruptions: “storingen” (breakdowns) will occur, emergency repairs will multiply, and restrictions will become common . Indeed, it’s already happening – weight limits have been imposed on certain old bridges (trucks and farm vehicles are detoured) and speed limits (down to 50 km/h) on aging viaducts like the Haringvliet Bridge to reduce stress on failing components . These are stop-gap safety measures, but they foreshadow a future of inconvenient and costly bottlenecks if proper fixes are not made. In a worst-case scenario, critical infrastructure could be forced to close for extended periods, something authorities try to avoid but admit may be “inevitable” without extra funding . The economic stakes are high: the Netherlands is a transport and logistics hub for Europe, and its competitive advantage rests on smooth connectivity. A major highway bridge closure or unreliable lock on the Rhine–Meuse delta can disrupt not only local traffic but international trade flows. Prolonged detours due to failing infrastructure would mean longer commutes, more traffic jams, shipping delays, and real financial losses for businesses. One analysis of Dutch waterways found that maintenance backlogs increase costs in unexpected ways – emergency fixes tend to be more expensive than planned works, and shipping stoppages can cost millions in idle time . In short, every year of delay in addressing the infrastructure deficit likely adds to the ultimate price tag and drags on economic output.

As 2030 approaches, the Netherlands finds itself at a crossroads eerily reminiscent of the 1960s – but in reverse. Back then, a sudden bounty of gas revenue built a modern nation. Today, the country faces the arduous task of rebuilding that aging infrastructure without a similar windfall. The “gas boom” legacy has turned into an “infrastructure bust” challenge. Policymakers, engineers, and financiers are urgently seeking a new formula to finance renewal: whether through user-pays principles, innovative funding models, or a recommitment of public funds. The coming years will likely see a mix of measures, negotiated carefully to balance Dutch aversion to tolls with the hard reality that something’s got to give. One thing is certain – without decisive action, the bills will only grow larger and the inconveniences more frequent. The Netherlands’ infrastructure, once a symbol of postwar prowess, is testing the nation’s resolve. In the words of one Dutch infrastructure report, “Intervention is inevitable to prevent further delays for citizens and businesses” . The hope is that this time, the interventions will be proactive investments – not emergency patches – ensuring that the roads, bridges and dikes built with yesterday’s gas money can continue to serve tomorrow’s Netherlands.

Sources: Historical revenue and budget figures ; current maintenance deficits and recent incidents ; industry and expert assessments ; policy debates and stakeholder quotes ; forward-looking projections .